Like many of our patrons, we received mail from some distant locales this holiday season. One package arrived from the Museum of South Texas History, whose curator sent us two pictures to add to our collection.

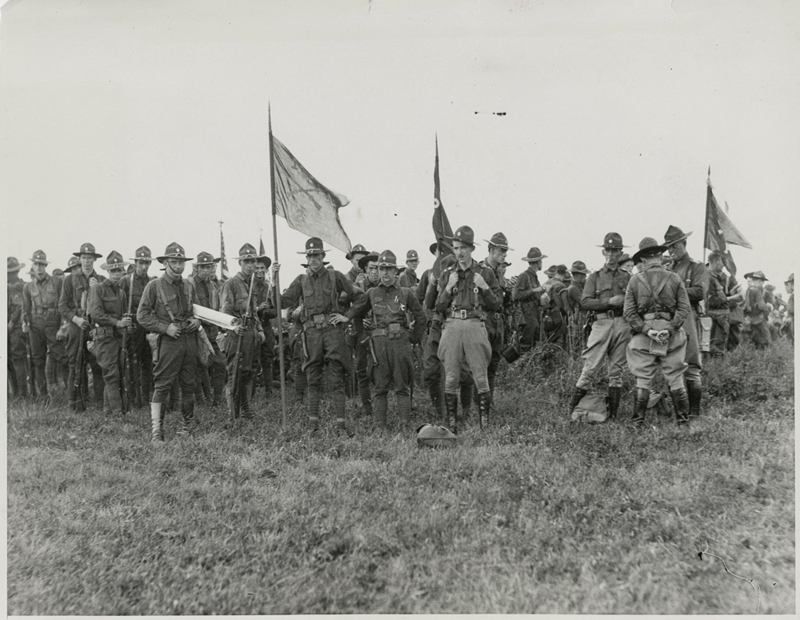

The images date back to 1933 and depict National Guard troops stationed in Brownsville during the coal strikes. Both were stamped for distribution through the Central Press Association and arrived with suggested captions taped to the back.

“BROWNSVILLE, PA . . . Pennsylvania National Guard troops sent to prevent violence in the coal regions establish their camp three miles west of Brownsville.” July 31, 1933.

“BROWNSVILLE, PA . . . MACHINE GUNNERS PRESERVE ORDER IN COAL STRIKE AREA. This 112th Infantry National Guard machine gun unit points the business end of a machine at the cameraman as it establishes itself in the bituminous strike area at Brownsville, PA. The militia has taken command of the situation under orders from Gov. Pinchot of Pennsylvania after 10 miners had been injured in the strike disorders.” July 30, 1933.

The year of 1933 was a volatile one for many industries as workers pressed for higher pay, shorter hours, and union representation. The strike that brought the National Guard to the Brownsville area erupted after a Labor-friendly speech by President Roosevelt. If all competing employers would agree to offer reasonable wages and hours, the president said, “then higher wages and shorter hours [would] hurt no employer.”

The message resonated with Fayette County’s miners. On July 25, 1933, the Uniontown newspapers reported that 4,000 local miners had walked off work — with many more to follow suit.

Picketers blocked roads and entrances to the mines. Fights broke out not only between the miners and company guards, but between the miners and those who were trying to cross their picket line. That might have been a fellow miner who tried to go to work (called a “scab” by the picketers) or just a child trying to deliver his father’s lunch.

Indeed, a healthy number of the picketers were the wives and offspring of the miners. Occasionally their behavior caused the State Police or Guardsmen to clear the picket lines, as noted in the August 1, 1933 Morning Herald:

Martin F. Ryan, one of the strikers, immediately protested the dispersal of the picket line and declared he would wire a protest immediately to Governor Pinchot. Lieutenant Urban replied:

“If anybody makes any disorder, your men or anyone else, we are going to grab him . . . We are here to keep the roads open and we are going to see that they are kept open.”

After the man was given a short talk he was turned loose. The militia ignored an elderly woman who stood nearby with rocks in both hands.

The fighting extended to Sheriff Henry E. Hackney and Pennsylvania Governor Pinchot, who disagreed over the possible declaration of martial law in the county. Their telegrams to one another were printed in the local newspapers, along with this full-page declaration by Sheriff Hackney (click to enlarge):

My favorite message had to be the H.C. Frick Company’s very terse response to Governor Pinchot’s accusations:

My favorite message had to be the H.C. Frick Company’s very terse response to Governor Pinchot’s accusations:

I am informed by the press this evening that you have charged the H.C. Frick Company with conspiring with the Sheriff of Fayette County in importing gunmen to act as deputy sheriff’s in the county. Please be informed that your statement in wholly without foundation.

Officials eventually closed the mines for the safety of those trying to cross the picket lines. At least one picketer was shot to death by company guards before the U.S. government intervened and ended the southwestern Pennsylvania strikes on August 8, 1933.

Many thanks to the Museum of South Texas History for thinking of us. Please take a minute to stop by their website and/or Facebook page!