My favorite part of working in the Pennsylvania Room is that each and every day, I’m surrounded by stories. They’re tucked into yearbook pages, scribbled in the margins of ancestry charts, and hidden away in old family letters. Whether I’m faced with tracing the history of a person, place, or event, I enjoy the challenge of piecing all the fragments together to form a single narrative.

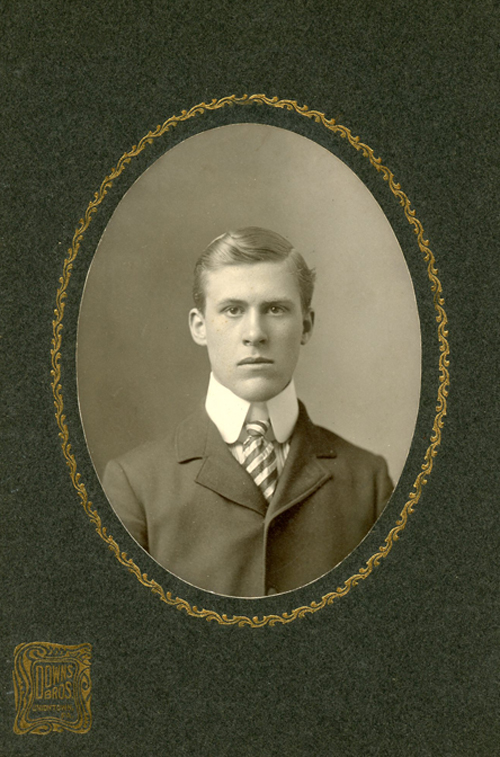

For the Stories in Stone segment, I’d intended to pick a headstone and document my research on the person buried beneath it. But for this first “episode,” my curiosity was sparked not by a tomb, but by a photo from our collection. Specifically, this one:

Newell Allton. Credit: Uniontown Public Library.

Sharp-looking guy, right? I spotted this picture while going through one of our many albums. When I took the photo out and flipped it over, I found “Newel Allton” written on the back. That was it. No date, no location — just a name.

Maybe you have a few photos like this in your own family albums. It can be daunting to start your research with nothing but a name, even if the person involved is an ancestor. After all, once a few generations pass, their life might be as unknown to you as that of a complete stranger.

Well, here’s the proper attitude in approaching a project like that: Challenge accepted!

In this case, I chose to start my research by checking the Pennsylvania Room’s obituary index, where I found a card that read “Allton, Newell R.”

Newell Allton’s card in the Pennsylvania Room’s obituary index. The card lists (1) his name, (2) where he was from, (3) the name of the newspaper in which the obituary or article about him was printed, and (4) the publication dates.

It surprised me to see the year 1910 listed on that card. Judging by his clothing and hairstyle, Newell appeared to have been photographed in the early 1900s. He had died a young man.

But how?

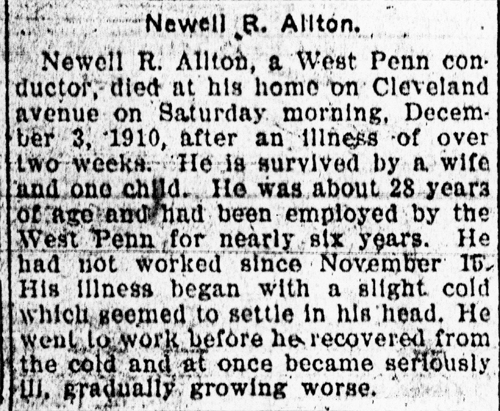

In order to find out, I looked up the editions of the Daily News Standard noted on the obituary index card. The first article was a death notice, and within its first few sentences, it provided me with the exact information I needed to propel my search along. Newell was a trolley conductor for West Penn, I learned, and was survived by his wife and child. He’d died in his home after being sick for more than two weeks. The obituary concluded:

“His illness began with a slight cold which seemed to settle in his head. He went to work before he recovered from the cold and at once became seriously ill, gradually growing worse.”

Newell Allton’s obituary, as published in the Daily News Standard on December 3, 1910.

On December 5, a few words were printed about Newell’s funeral. His burial at Oak Grove (a Uniontown cemetery that fronts on Route 40) was well-attended by his coworkers at West Penn, some of whom acted as pallbearers. The company even sent a floral wreath in the design of the West Penn logo to rest on his grave. The gesture says something about how Newell was regarded by others, I think.

The man was laid to rest under a plain, flat tombstone just a day after his death. His story ended there, but now we’ll learn what came before.

![]()

With all this new information in mind, I next turned to the censuses. Considering the dates of Newell’s birth (1884) and death (1910), I could reasonably expect him to be picked up in the 1890, 1900, and possibly the 1910 censuses.

Well, scratch the 1890 Census right away. A 1921 fire destroyed nearly all of it, and none of the remaining records pertain to Pennsylvania.

I jumped ahead to the 1910 Census, which reported a “Newell R. Allton” as the head of a young family. While the age and family status were correct, the employment information confirmed to me that this was the Newell Allton that I was looking for.

Trade or profession? Conductor.

General nature of industry? Street car.

Next, I chose to flip back to the 1900 Census. There I found a 15-year-old “Newal Alton” living with the Coffman family, along with a “Velena Alton.” They were listed as the nephew and niece of the Coffmans. Had they been orphaned prior to 1900?

Returning to the Fayette County Genealogy Project, I looked at the other Alltons on the tombstone photo list. There, a particular couple caught my eye: John and Sarah Louisa Allton. If you take a look at John and Sarah Louisa’s ages, you’ll see that they could easily have been Newell and Velena’s parents. Both also passed away before 1900. I confirmed my hunch by finding Newell Allton’s marriage certificate, which lists his parents names: “John and Louisa.”

With each piece of information, new venues for research appeared. For John and Louisa’s causes of death, I could turn to the county’s records; if I wanted to see how Newell’s son got along, I might flip through some local yearbooks.

But here’s what was really bugging me: Was the Newell Allton in the photograph definitely the same person as the one in the records? While the evidence was strong, I wished I could be completely sure.

And that’s where a bit of dumb luck came into play.

A couple weeks after I began my research, a Pennsylvania Room volunteer called my attention to a list of donations made to the room nearly twenty years ago. According to that list, there were not one, but two photos of Newell Allton in the collection. I tracked the second picture down, and this is what I found:

Credit: Uniontown Public Library.

While the other two people in the photo are unidentified, Newell is recognizable on the far left. Conductor operating a street car? Check and check! The Newell Allton in the portrait was indeed the orphaned son, young father, and West Penn employee I had learned about in the records.

Now that the photos have been slipped back into their sleeves and returned to their places in the Rare Book Room, I find myself curious about our area’s trolley system. Check out the one in the photo above. Doesn’t it seem to be open-air? Was that a year-round thing?

Yet another subject to research!

Credit: Uniontown Public Library.