This article was researched and written by PA Room volunteer Paul Davis. Thanks to Paul for contributing!

Fayette County has a prominent industrial history and has long been synonymous with the coal boom of the 19th and early 20th century. Growing up, I remember my mother telling me that Uniontown had contained a large number of millionaires; in 1907, at least 13 called the city home and their wealth grew out of the mining industry.[i] Today, coal is still at the root of what the locals remember as “the good old days.” However, before mining played its hand in our area’s history, another industry thrived in Fayette County: iron-making.

Iron has been utilized for thousands of years. People created numerous items using the material, including cooking utensils, money, and weapons. However, while it’s a naturally-occurring element, iron ore is not especially useful in its raw state. In order to make it stronger and more durable, it must first go through a chemical reaction to remove its oxygen content, a process that is achieved through an iron furnace. These structures began to dot the southwestern Pennsylvania landscape in the earliest days of pioneer settlement and would not go away entirely for nearly two centuries.

A Brief History of the Industry

In America, iron was first made by colonists from Europe. The Native Americans used no iron products. Fortunately for the colonists, the three material ingredients used to make it—iron ore, limestone, and lumber for charcoal—were abundant in the New World.[ii] The first successful iron furnace in America was built in 1643 near Lynn, Massachusetts on the Saugus River. Pennsylvania’s first iron furnace was built in 1720 in Berks County and was named Colebrookdale Furnace. Over the next fifty years many iron furnaces were erected in eastern Pennsylvania, including Valley Forge, where George Washington and the Continental Army spent the brutal winter of 1777-1778.[iii]

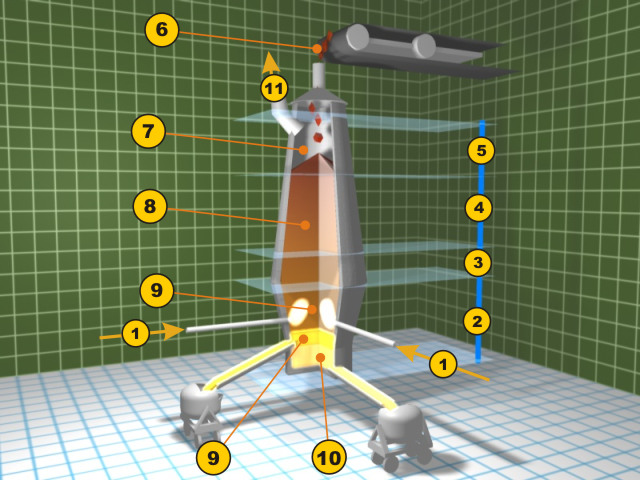

A modern Blast furnace but the process is essentially the same. Raw materials loaded in the top, blowing air in the bottom and collecting molten iron from the bottom. Source: Wikipedia

Early charcoal fueled furnaces looked like flat-topped pyramids about 25 to 35 feet high. They were made of stone or brick and the tops were open to load the raw materials, which included iron ore, a material high in carbon (such as charcoal or coke), and limestone. As a result, furnaces were commonly built near a hill side to make loading easier, and shed-like structures were built nearby to house the necessary ingredients.[iv]

After the raw materials were mixed into the heated furnace, air was blown in to further raise the temperature. The burning charcoal or coke created carbon monoxide, which pushed the oxygen out of the iron ore.[v] Once the temperature was raised to 2700 degrees Fahrenheit, the ore began to liquefy. The liquid iron would then trickle down through the furnace and eventually flow out. Meanwhile, the added limestone removed any acidic impurities in the iron and produced a waste product called “slag.” These furnaces typically operated for nine months of the year, only closing in unbearably hot summer months or in the harshest part of winter, when freezing interfered with the water wheel.[vi]

Iron furnaces required a great amount of money and a large amount of land with the proper raw materials. Accordingly, many early furnaces were erected near iron ore seams and wooded areas. Transportation away from the furnace was also taken into consideration. Building a furnace with easy access to roads was necessary in order to ship out the product to market, and many had to be near streams or runs because of the need for water power.[vii] Fayette County contained plenty of untapped natural ore. Moreover, its hills and natural streams made it an ideal location to pursue this rising industry.

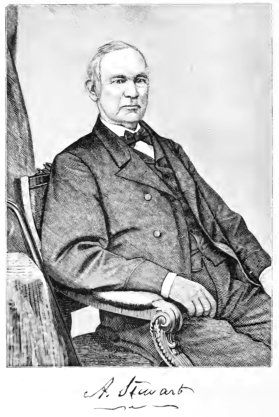

Andrew Stewart, the man who started Wharton Furnace in 1837. Source: History of Fayette County by Franklin Ellis, 1882.

The operation of an iron furnace required a number of different workers. At the top was the iron master who started and owned the furnaces and oversaw their activity. The ironmaster usually had a clerk to help with records and below that there were the laborers.[viii] The laborers were men or boys and their number varied from furnace to furnace. One source mentions 60 to 80 workers onsite with 30 to 50 horses.[ix] Another source claims about 30 workers with that number cut in half for shifts. Because operations were continuous, half of the workers worked in the day and half at night.[x]

As the industry was moving into the mid-19th century, iron-making techniques evolved with the advancements in science and technology. Early on, hunches and experience were how iron makers made their calculations, but as the century progressed, the chemistry of the process gained respect. The chemical makeup of the ingredients and how they reacted together became a serious field of study. Sons of ironmasters were sent to universities to educate them on the nature and the nuances of the job, and even poorer young men were taking night classes so they could attempt to rise through the ranks of the industry.[xi]

By this time steam engines were replacing water wheels to blow the bellows of air into the furnace, while the furnaces themselves were moving into more urban areas for ease of access. Advances in fuel were also making things easier. Coke, a product of coal, was rising as a cheaper and easier alternative to charcoal, as the once-massive forests were chopped down for roads, farms and other settlements. Coke also produced better quality iron.[xii]

Eventually iron’s popularity began to wane. Steel was a superior product and by the 1860s it became cheaper and quicker to make due to technological upgrades.[xiii] Iron furnaces could not match the output of the steel factories, where mass production techniques were applied. Steel factories also called upon more unskilled workers than the iron furnace, expanding their available workforce.[xiv] Slowly, steel began to usurp iron as the dominant metal, quickly stealing the railroad market and proving itself to be a better building material. By 1883, the annual output of steel equaled that of iron and in the coming years steel supplanted it.[xv]

For a time, independent iron-making firms survived in niche markets by manufacturing high quality goods with a greater degree of detail than steel companies would take on. By focusing on specialized products like wrought iron pipes, nuts, bolts, and nails, they were not in direct competition with steel and could therefore survive into the 20th century.[xvi]

Iron in Western PA

Ruins of Alliance Furnace near Jacobs Creek. Source: History of Fayette County by Franklin Ellis, 1882.

Fayette County was the jewel of iron-making in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. Between 1789 and 1837, 20 furnaces were built in the county, the most on the western side of the state.[xvii] As Gerald Eggert put it, “For several years Fayette County was the west’s great center of iron production, supplying Pittsburgh and the Ohio and Mississippi Valleys beyond with castings and pig and bar iron.”[xviii] Fayette County’s rise to the top of the industry began when three business men from eastern Pennsylvania, William Turnbull, John Holker, and Peter Marmie, brought their resources together and built Alliance Furnace on Jacobs Creek near Perryopolis in 1789.[xix] Alliance Furnace was the first iron Furnace on the western side of the Allegheny Mountains and it contributed to the iron industry right away, producing shot and shells for Mad Anthony Wayne’s expedition against the Native Americans in the late 19th century.[xx]

As more people crossed over the mountains to western Pennsylvania, the industry grew, and the area saw its own generation of iron masters. Isaac Meason,a prominent county resident in the early part of its history, built Center Furnace in 1815 near Glade Run.[xxi] He also built Union Furnace 1 in 1791 on Dunbar Creek, which was the second furnace in Western Pennsylvania. It was replaced by a larger furnace in 1793, slightly downstream named Union Furnace 2. In 1844 it was then enlarged and named Dunbar Furnace. Dunbar Furnace was a testament to the tenacity of the iron industry. It was bought by the Semet-Solvey Company and operated until 1930 when it was finally closed due to the Great Depression.[xxii]

Isaac Meason built other furnaces, one of which has been restored and can be visited today. Mt. Vernon Furnace is located in Bullskin Township, near Mounts Creek, and was built between 1795 and 1801. Its flame was permanently blown out in 1830. In 1991, it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places. Researchers have been able to determine that the iron the furnace created became a variety of tools, such as cooking utensils, kettles, and iron bars. These products were transported to Connellsville and then shipped down the Youghiogheny River for further distribution.[xxiii] In 2003, the land around it was purchased by the Bullskin Township Historical Society with the intention of restoring the furnace.[xxiv] That restoration is now complete and the furnace can be visited. It is located near the Bullskin Twp. Fairgrounds and the Bullskin Twp. Historical Society, in a village known as Wooddale.[xxv]

Another furnace in Fayette County is available for the public to visit. Wharton Furnace was constructed by Andrew Stewart (the namesake of Stewart Township) near Chaney Run in 1837 and first blown in 1839. It did not last very long as it stopped producing before 1850, however the Civil War gave it a second life. The furnace produced cannonballs for the Union Army during this time, but when the war ended, it could not find a place in the industry. These periods of inactivity can be explained due to the fact that the location is rather isolated. It had no easy access to railroads or major waterways, and therefore could not ship its product effectively. Its flame was finally blown out for good in 1872. The Stewart family continued to own the property until 1961 when the furnace was restored by a coalition between the Fort Necessity Lions Club, the Western Pennsylvania Historical Society, and Myron Sharp. In 1991 it was placed on the National Register of Historic Places.[xxvi] It is located on Wharton Furnace Road, about two miles south of Route 40. The property is owned by the State Department of Conservation and Natural Resources.[xxvii]

Wharton Furnace, summer 2017. The author is standing to the right side for scale. Photo by Paul Davis.

Conclusion

The iron furnaces of Fayette County were extremely important to the growing industry of the nation. Iron helped build and arm the nation in its most dire times and Fayette County and Western Pennsylvania in general were at the forefront. Even as the iron industry was being overtaken, steel moved in and continued to let Western Pennsylvania build the country. In addition, the importance of the iron industry helped bring about Fayette County’s other main industry: coal. Coal that was mined in this area was turned into coke and fed the iron furnaces in the mid- 19th century. The abundance of iron furnaces in the area may have started a chain reaction that helped Western Pennsylvania become a leader of industry throughout much of its history.

[i] “Uniontown’s Bunch of Millionaires” Pittsburgh Gazette Times June 12, 1907. Quoted in John A Enman, Another Time Another World: Pennsylvania Bituminous Coal, Coke, and Communities (Uniontown: Path/Work Voices, 2010), 39-43

[ii]Gerald G. Eggert, The Iron Industry in Pennsylvania (Middletown PA: The Pennsylvania Historical Association, 1994), 1

[iii]Myron Sharp and William Thomas, A Guide to the Old Stove Blast Furnaces in Western Pennsylvania (Pittsburgh: The Historical Society of Western Pennsylvania, 1966), 2

[iv] Eggert, 5-6

[v] “Iron and Aluminum” BBC, 2017 accessed August 3, 2017. http://www.bbc.co.uk/education/guides/zfsk7ty/revision/4

[vi] Eggert, 8-10

[vii] Eggert, 5-6

[viii] Eggert, 10-11

[ix] Sharp and Thomas, 3

[x] Eggert, 10-11

[xi] Eggert, 62-63

[xii] Eggert, 63

[xiii] Eggert, 79

[xiv] Eggert, 88-89

[xv] Eggert, 79

[xvi] Eggert, 88-90

[xvii] Fayette T & R Bureau. Old Iron Furnaces and elated Works in Fayette County in the Laurel Highlands. Uniontown , PA: Fayette County Development Council.

[xviii] Eggert, 33

[xix] Sharp and Thomas, 43

[xx]Lee Elby, “Iron played a big part in Fayette’s history,” Tribune Review, November 26, 2000. A2

[xxi] Sharp and Thomas, 45

[xxii] Elby, A2

[xxiii] “History of Mt. Vernon Furnace,” Bullskin Township Historical Society, 2017, accessed July 8, 2017, http://www.bullskintownshiphistoricalsociety.org/mt__vernon_furnace.

[xxiv]Amanda Cochran, “History, set in stone: Bullskin offers tours of Mt. Vernon iron furnace,” Tribune Review, May 28, 2006. B1

[xxv] Bullskin Township Historical Society

[xxvi] National Register of Historic Places, Wharton Furnace, Wharton Township, Fayette County, Pennsylvania, OMB No. 1024-0018, Available [Online]: http://www.dot7.state.pa.us/CRGIS_Attachments/SiteResource/H094504_01H.pdf [July 22, 2017]

[xxvii]Elby, A2