The Marquis de Lafayette in his Continental Army Uniform. (via Wikipedia)

This article was researched and written by PA Room volunteer Paul Davis. Thanks to Paul for contributing!

The Marquis de Lafayette became one of the most influential figures in the history of the Western World. He was known as “The Hero of Two Worlds” because of his actions in the American Revolution and his involvement in the French government, but also as “the most hated man in Europe” because of his ideals and actions during the French Revolution.[i] He was a man who fulfilled many roles in his lifetime, including soldier, politician, idealist, and troublemaker, among others. Here in America, his involvement and enthusiasm gave an air of legitimacy to the Revolution. The support of a young noble such as Lafayette from an “established” European nation was a great boost for the morale of the American people. Lafayette was celebrated the nation over for his involvement in the Revolution and he adopted America as his second home. In 1824, when Lafayette was 66 years old, he was invited to return to America for a reunion tour of the country he helped liberate. During this tour, Lafayette traveled east on part of the National Road and stopped just before the Allegheny Mountains in a little county bearing a familiar name. While there, he met with an old friend and former U.S. Secretary of Treasury and was given quite the splendid reception by the locals.

Who was the Marquis?

Adrienne de Lafayette (via Wikipedia)

Born Marie Joseph Paul Roch Yves Gilbert de Lafayette on September 6, 1757 in Chavoniac in central France, he was known as “Gilbert” by those closest to him. The future Marquis de Lafayette was the newest member of a noble family with a long military history. Though his father had died after being struck with a cannonball at the Battle of Minden in 1759, Lafayette aspired to continue his family’s military reputation. Once he married his wife Marie Adrienne Francoise de Noailles (known as Adrienne) in 1774, he was able to acquire the rank of captain of the Noailles regiment thanks to the favor he gained with his father-in-law. Lafayette soon became a rising star in the French noble scene.[ii]

Lafayette was inspired by the American Revolution and captivated by its ideals of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness. In 1777, at the age of 19, Lafayette decided to leave France and aid the American cause. It should be noted that many in the French court were not happy with his plan, including his father-in-law, who threatened to jail Lafayette to prevent him from leaving. As a result, Lafayette had to travel cross-country, in disguise, to meet his ship and not attract attention.[iii] He was welcomed in America with open arms. He became an aide-de-camp of General George Washington, whom he saw as a father figure for the rest of his life. He commanded units at the Battles of Brandywine, where he was wounded in the leg, and he was with the army at Valley Forge. At Yorktown, he put the pressure on British General Cornwallis until Washington and French forces could arrive and force the British surrender. He served for the Continental army for free and even had to pay his men out of his own pocket at times.[iv]

Returning to France in 1781 as “The Hero of Two Worlds,” Lafayette strove to improve the political situation in his home country. He acted as a go-between during portions of the French Revolution, fighting for fair rights for the citizens of France while he also protected the monarchy as the commander of the National Guard. He also drafted the Declaration of Rights of Man and of the Citizen, a document that borrowed much from America’s own Declaration of Independence.[v] Eventually, things spiraled out of control for him and he was forced to flee France. He became “the most hated man in Europe.” He was despised by the French radicals for his relationship with the monarchy and reviled by the nobles of Europe for his ideals, which took away the absolute power of the kings and queens of the continent.[vi] He was captured by Austrian forces in 1792 and held prisoner until 1797. After he was released, he eventually returned to France but kept a relatively low political profile until 1815, when he was one of leading voices in the Chamber of Deputies to argue for Napoleon’s abdication of the throne.[vii]

The Reunion Tour

Lafayette’s invitation to return to America had both political and symbolic purposes for President Monroe. By the 1820s many of the heroes of the American Revolution were gone. The nation would have to strive on its own with a new generation, one that had no personal recollection of that fight. President Monroe thought that inviting the last surviving General from the Revolution would act as a symbol of entrusting the future of the country to the next generation. Furthermore, a visit by the “Hero of Two Worlds” would show support on both sides of the Atlantic for the Monroe Doctrine. The Monroe Doctrine essentially stated that Europe should stay out of the affairs of the “New World” (Central and South America) and in turn the United States will in turn stay out of the affairs of the “Old World” (Europe). There was a great deal of dissent about this Doctrine, especially in Europe, but Monroe hoped that by inviting Lafayette, it would act as a sign of friendship between the two continents despite the ongoing tension.[viii]

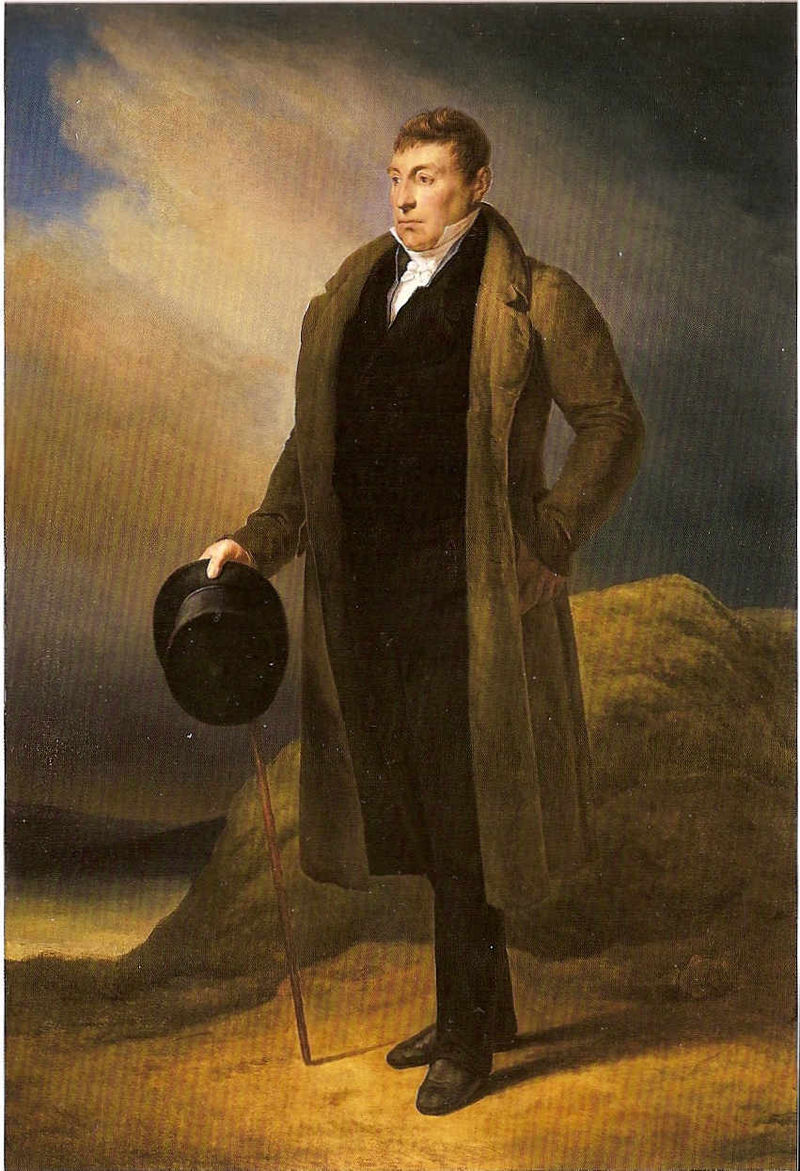

1824 Portrait of Lafayette. (via U.S. House of Representatives)

The timing of this tour was perfect for Lafayette. He no longer had a seat in France’s Chamber of Deputies and his relationship with King Louis XVIII was less than ideal. Getting out of France and seeing the country he helped create was a tantalizing idea. However, many in France thought America had ulterior motives, including members of the monarchy. King Louis XVIII and his court were insulted by the invitation. They were convinced that America was trying to seize the French West Indies and they were going to make Lafayette the Governor to make the transition easier. The king did not prevent the visit but made Lafayette’s departure very uncomfortable. When a crowd gathered around the American Consul to see Lafayette off, the king ordered that the crowd be dispersed forcefully by troops on horseback. Despite this unpleasantness, Lafayette set out in July 1824 for America with his son George Washington de Lafayette, as well as his secretary August Lavasseur.[ix]

He arrived in August 1824 to a grand celebration. Everywhere he went he was treated to crowds of people eager to see the hero of the Revolution for themselves. His journey began in New York City, and from there, he headed to Boston. A main focus of his trip was visiting old friends. From Boston, he headed to Quincy where he met with John Quincy Adams, who was running for President at the time. He headed back to New York and visited such towns as Albany and toured West Point. He went south from there to Philadelphia, Baltimore, and Washington D.C., where he stayed with President Monroe at the White House. He stayed in D.C. for the winter and was there when John Quincy Adams was elected President. Upon his presentation to both the Senate and the House of Representatives, Congress saw fit to award him a payment of $200,000 for services rendered in the American Revolution.[x]

After the winter let up, Lafayette continued his journey south visiting such landmarks as Yorktown and Mount Vernon. He saw some familiar faces when he visited Thomas Jefferson at Monticello and James Madison at Montpelier. He continued South through the Carolinas and Georgia and turned west to New Orleans. Along the way, he passed through many territories owned by Native Americans and met with delegates from various tribes. From New Orleans, he headed north via the Mississippi River to St. Louis, where he met General William Clark, of Lewis and Clark fame. He then traveled up the Ohio River to stop in Tennessee and Kentucky, where he met Andrew Jackson at Hermitage.[xi] There was a bit of a scare when his steamboat ran aground in the middle of the night and everyone had to abandon ship. Although no one was injured, the party lost all of their possessions. They were stranded in Kentucky until the next morning when another steamboat headed for New Orleans rescued them. When the captain found out that Lafayette was one of his passengers he immediately turned around and took the party to Louisville, Kentucky. The journey continued up the Ohio, where Lafayette met General William Henry Harrison, hero of the War of 1812 and future President of the United States. He then traveled to a small county in the southern corner of Western Pennsylvania where the locals gave him quite the warm welcome. [xii]

Lafayette in Fayette County

Albert Gallatin. Daily News Standard. July 4, 1896,

Lafayette stopped here in Fayette County, Pennsylvania for a few reasons. For one, the county was named after him, and he was eager to see places named after himself. (Earlier on his journey, he stopped at Fayetteville, North Carolina, the first American town named in his honor.[xiii]) The other reason to stop in our area was to see his friend Albert Gallatin. Gallatin was a staple of early American politics. He held many positions, including U.S. Secretary of Treasury from 1801 to 1814 and he and Lafayette became good friends when Gallatin was the U.S. Minister to France from 1816 to 1823. This would have been the first familiar face he would have seen for months after his long trek through the Southern and Western States.[xiv]

His procession arrived via Washington, Pennsylvania on Thursday, May 26, 1825. The group had breakfast at the Hill Tavern (now known as the Century Tavern) in Hillsborough (now Scenery Hill) on the National Road. Lafayette then made his way to Brownsville. They crossed the Monongahela River around noon on a special barge and entered Fayette County. Waiting for him on the barge were 24 young girls, dressed in white, representing the 24 states. When Lafayette made landfall the girls all crowned him with flowers they were carrying. Unfortunately, not much else is known regarding his time in Brownsville, but it is assumed to have been quite the celebration. An unsourced report claimed that a messenger had to be sent to make the party move faster as they were behind schedule to arrive in Uniontown.[xv]

The party was finally spotted east of Uniontown at about 5:30 PM on May 26, at which time a discharge of 12 artillery cannons announced Lafayette’s arrival to the citizens of town. He proceeded into town via Main Street and passed under two arches made specifically for the occasion.[xvi] One of the arches was placed at the intersection of Morgantown St. and Main St. and the other arch was placed at the entrance to the courthouse. They were decorated with laurel and wreathes of roses. In front of the courthouse, a pavilion was erected to receive Lafayette. Surrounding the pavilion were seats exclusively for the women in the audience, the only exception being made to Revolutionary War veterans so they could view their former officer better. Lafayette pulled up to the courthouse at about 6:00 PM and was met by Gallatin and General Ephraim Douglass, who had been waiting since 11:00 AM.[xvii]

When he arrived, Lafayette greeted his hosts and then he and Gallatin addressed the crowd. Numerous toasts were given by everyone involved. Afterward the party retired to the Walker Hotel (which later became the Central Hotel and eventually the site of the Gallatin Bank Building at 2 W. Main St.) for supper and to rest. At about 6:00 AM the next morning Lafayette and his party set out for Gallatin’s home of Friendship Hill.[xviii]

The procession stopped briefly at New Geneva, not far from Gallatin’s home, where he was met with throngs of people once again. They escorted him through the town up to Friendship Hill, which was then thrust open to the public for a celebration. A free meal was given to as many people as possible who came to see the hero and drinks were passed around freely. Lafayette only stayed one night at Friendship Hill. He was given a reception on his way back to Uniontown the next morning in New Geneva again, when the ladies of the town made great efforts to strew garlands of flowers in front of the carriage as he passed. In Uniontown, he was once again met with crowds of people, eager to catch a glimpse of this larger than life figure.[xix]

Recollections

There were numerous recollections of his time here in Fayette County. Mary A. Getzendanner recalled that Uniontown was lit up on the evenings Layette was present. The arches lining Main Street were illuminated with candles and every house on Main Street had candles in their windows. She even remembered her “childish heart” being stirred at the classic aura Lafayette possessed as he passed through town. (She was 12 at the time.) William W. Clark of Connellsville Street remembered that work was suspended for a time so that the citizens could pay respects to Lafayette.[xx]

Joseph Hayden of Union Street recalled, “Lafayette was a great man…and I had heard of him ever since I was old enough to remember anything.”[xxi] He described the streets as being packed with people and a buzz of excitement in the air. He recollected Lafayette being polite to the crowds as he passed through. The Marquis held his hat in his hand and bowed to people on both sides of the street, making sure to acknowledge them. Lafayette was, as Hayden saw it, “royally entertained during his stay in Uniontown.”[xxii]

Lafayette’s time passing through New Geneva left impressions on numerous citizens as well. Julia Speelman of McClellandtown recalled getting the town ready the day before and was disappointed when the Marquis’ visit was delayed. She recalled all the girls in town wearing white and when Lafayette passed through the crowds, he walked with a limp. Charles Baffle of New Geneva recalled the men and boys meeting the procession on top of the hill and escorting them down into town. Once Lafayette’s business there was concluded, he continued on to Friendship Hill and Baffle remembered following the procession and receiving a free meal. It must have been substantial because he remembered his mother and sisters not preparing any food that evening. James Davenport also recalled meeting the procession on the hill, and that the town was swept clean, streets and alleys included, in preparation for the esteemed visitor.[xxiii]

Lafayette also passed through Perryopolis, where Elizabeth Porter witnessed the procession. She remembered crowds of people from the countryside coming into town to see Lafayette. Women were all dressed in white in preparation and held bouquets of white roses. When the General was near they threw the flowers in front of his carriage. At one point the procession stopped and Lafayette was lifted out of the carriage by four men who carried him on their shoulders for the crowd to see.[xxiv]

Despite the attention that Lafayette attracted, no disturbances occurred and everyone was on their best behavior. As explained in the June 7 edition of the Genius of Liberty,

“Although the crowds which every where [sic] attended the general while in our county, was [sic] immense, yet have we not heard of one solitary occurrence, to interrupt the pleasure and festivity which all were so anxious to indulge in; harmony and unanimity of feeling, was [sic] conspicuous throughout.” [xxv]

The Journey Concludes

Lafayette’s visit to Fayette County lasted only three days, but the reception he was given showed just how important the Marquis was to the people of the area. After leaving Fayette County he traveled north visiting such towns as Perryopolis and Elizabeth, where he met more fanfare before continuing his journey to Pittsburgh.[xxvi] After seeing the confluence of three rivers he traveled north to Buffalo and Niagara Falls. The party then went east to Boston, via the partially completed Erie Canal, for the 50th anniversary of the Battle of Bunker Hill. Finally, Lafayette traveled south to New York for the Fourth of July and then on to Washington, D.C. He rested in the capitol long enough to celebrate his 68th birthday on September 6, 1825, and the very next day he left for France on the newly outfitted frigate, The Brandywine.[xxvii]

The Marquis and Adrienne’s final resting place in Picpus Cemetery in Paris. (via TripAdvisor)

Upon his return to France, Lafayette continued to be a part of French politics in a variety of ways. He regained his seat in the Chamber of Deputies and during the July Revolution in 1830 he even directly endorsed Louis-Philippe as King, causing his accession.[xxviii] Eventually age caught up with Lafayette and while attending a funeral in February 1834 he became very ill. He became well enough to walk around his home and write letters and on May 9, 1834 he decided to go on a carriage ride. He was caught in a passing thunderstorm, which left him drenched, and he soon relapsed. He passed away from pneumonia on May 20, 1834.[xxix]

Lafayette was larger than life to the American people. He was still a teenager when he arrived in America to fight for the freedom of a country and a people to whom he owed no allegiance. The plight of the Revolution inspired him to act. The American people had learned of this almost mythical figure and had to get a glimpse of him with their own eyes and say thank you to a man they felt they owed so much.

Author’s Note: I’d like to thank Maria Sholtis, Curator of the Library’s Pennsylvania Room, for her help. For those of you who are interested, there is so much more to Lafayette than I included in this article. I highly recommend reading up on him yourselves. The Uniontown Library has a variety of books on the subject and the Pennsylvania Room has plenty of information too. Poke around into his history and you’ll find even more fascinating elements.

[i] Harlow Giles Unger. Lafayette (Hoboken NJ: John Wiley and Sons, 2002) 286.

[ii]Gonzague Saint Bris, Lafayette the Hero of the American Revolution (New York: Pegasus Books, 2010) 18-19, 28-30.

[iii]Bris 81

[iv]Biography.com editors, “Marquis de Lafayette Biography,” Biography.com, December 21, 2015, http://www.biography.com/people/marquis-de-lafayette-21271783 (accessed February 14, 2017).

[v] Biography.com editors “Marquis…”

[vi] Unger 286

[vii] Biography.com editors. “Marquis…”

[viii] William Jones, “Lafayette’s Visit to the United States,” The Schiller Institute, November 2007, accessed February 4, 2017, http://schillerinstitute.org/educ/hist/lafayette.htm

[ix] Unger, 349

[x] Jones

[xi] Jones.

[xii] Unger, 358.

[xiii] Unger, 357

[xiv] Edgar Ewing Brandon ed. & comp. A Pilgrimage of Liberty: A Contemporary Account of the Triumphal Tour of General Lafayette Through the Southern and Western States in 1825, as Reported by the Local Newspapers. (Athens, Ohio: The Lawhead Press, 1944) 365.

[xv] Brandon ed. & comp., 364-365

[xvi]“Just 79 Years Ago,” Daily News Standard, May 26, 1904. 1, 4

[xvii] Brandon ed. & comp., 366-367

[xviii] Brandon ed. & comp., 367-375.

[xix] Brandon ed. & comp., 375.

[xx]“Just 79 Years Ago,” Daily News Standard, May 26, 1904. 1, 4.

[xxi]“Just 79 Years Ago,” Daily News Standard, May 26, 1904. 1, 4.

[xxii]“Just 79 Years Ago,” Daily News Standard, May 26, 1904. 1, 4.

[xxiii]James Ross, “The Visit of La Fayette (sic),” DailyNews Standard, July 4, 1896.

[xxiv]“Just 79 Years Ago,” Daily News Standard, May 26, 1904. 1, 4.

[xxv]Genius of Liberty, June 7, 1825 quoted in Edgar Ewing Brandon ed. & comp. A Pilgrimage of Liberty: A Contemporary Account of the Triumphal Tour of General Lafayette Through the Southern and Western States in 1825, as Reported by the Local Newspapers. (Athens, Ohio: The Lawhead Press, 1944) 375.

[xxvi] Brandon ed. & comp., 376-377

[xxvii] Jones.

[xxviii] Biography.com editors. “Marquis…”

[xxix] Unger, 376-377