If you live in Fayette County, you likely heard about the railroad cars that derailed behind the courthouse last week. Happily, no one was injured and no hazardous materials were spilled. There were no disruptions at the library, though we did listen to the steady thrumming of an engine for a few days while part of the train idled nearby.

I often come across railroad and trolley accidents while working with the PA Room’s obituary index. Still, the deaths I see were usually caused by passenger error — a person attempted to hop onto a moving train and lost their grip, for instance, or they got hit while walking the tracks.

There is one local railroad catastrophe that has clung to my memory, however: the wreck of the Duquesne Limited.

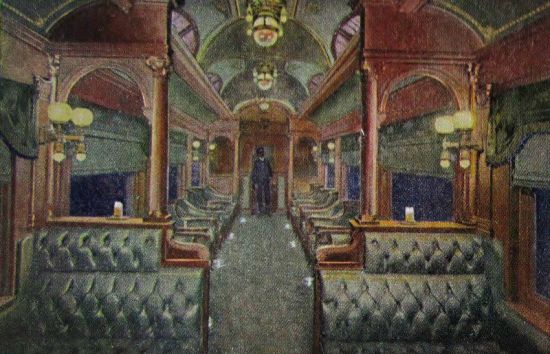

The smoking car on the Pennsylvania Special, a train belonging to a rival of the B&O: the Pennsylvania Railroad. (Wikimedia Commons)

It happened on the evening of December 23, 1903, about seven miles outside of Connellsville. The Limited was the fastest train in the Pittsburgh Division of the B&O Railroad and was running at a 60 M.P.H. clip when it came to a sharp curve at Laurel Run. It wasn’t unusual for trains to take that turn at speed, since the track was solid and — as the Courier pointed out — “passenger engineers bent on making their schedule do not shut off when taking the curve.”

Many of the train’s passengers were bound for Philadelphia, and considering the date, more than a few must have been traveling for Christmas. One Mr. Good of McKeesport was heading to New York to join his fiancée, who was en route from England to marry him. By nightfall a crowd of travelers had retreated to the smoking and dining cars to socialize.

They came to the Laurel Run curve around 7:45 P.M., unaware that a freight train had dropped a load of railroad ties across the eastbound tracks.

Satellite capture from Google Maps of the Duquesne Limited’s riverside path.

The pin marks the area of Laurel Run.

At impact, the entire train derailed — the locomotive, as well as its six coaches and its smoking, dining, baggage, and sleeper cars. The cars carrying passengers tipped off the rails, but didn’t tumble into the Youghiogheny; despite the derailment, the Courier reported, “the passengers in the Pullman cars were not shaken up much.” Those aboard the dining car also survived to help others escape.

Rather, it was the crowded smoking car that featured in the most horrific part of the wreck. The smoker collided with the locomotive and was gouged open by the steam dome, an apparatus that was fitted to the top of the engine’s boiler and covered its main steam pipe. The dome cracked open, and in an instant, the passengers inside the smoker “were literally cooked alive.” The Courier wrote:

Wrecked and battered open as it was, every ounce of steam from the engine poured forth its hissing messenger of death. From end to end the scalding cloud shot across the interior of the car. Not a single passenger escaped the deadly summons to another world.

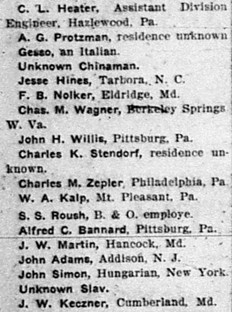

Part of the casualty list from the Daily News Standard. Note that the unidentified victims were referred to as “Unknown Chinaman” and “Unknown Slav.” Another article pointed out that most of the dead were English-speaking, as if that made the situation more tragic.

Indeed, most of those who were killed were riding in the smoker at the time of the crash. Further tragedy was prevented by the Limited‘s baggage master, who rushed out with a handful of lit matches to flag down another oncoming passenger train. The second locomotive reportedly stopped just yards from the wreck.

When help arrived, the victims were taken to City Hall in Connellsville, where prisoners were released to make room for the sixty-five deceased. The Daily News Standard remarked that this loss of life, “even in these days of colossal casualties, [was] most shocking to contemplate.”

The new century had certainly seen its share of sensational accidents. In 1900, a washed-out bridge sent a train and thirty-nine of its passengers to their doom in Georgia; the next year, a locomotive pulling part of Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show collided with another, injuring passenger Annie Oakley and killing a large number of circus animals. Then, less than two months before the Duquesne Limited‘s wreck, a crash in Indianapolis killed fourteen members of the Purdue football team.

Add to this mining and other industrial accidents — not to mention natural disasters like the 1900 Galveston Hurricane, and outbreaks of disease or warfare — and one can understand the Standard editor’s sentiment. But 1903 wasn’t done yet. Within a few days, newspapers across the country would be reporting on the Iroquois Theatre Fire, one of the deadliest in American history.

![]() If you can handle the grisly details, an account of the Laurel Run crash can be read on the Fayette County Genealogy Project’s website. The blame for the accident was eventually placed on those who loaded the timber on the freight train, and a bit of research reveals that the B&O continued to operate a train called the Duquesne Limited for decades after the disaster.

If you can handle the grisly details, an account of the Laurel Run crash can be read on the Fayette County Genealogy Project’s website. The blame for the accident was eventually placed on those who loaded the timber on the freight train, and a bit of research reveals that the B&O continued to operate a train called the Duquesne Limited for decades after the disaster.

Mr. Good, who had anticipated meeting his soon-to-be wife at Ellis Island, was killed in the crash. She only received the news when she arrived at New York on Christmas.

Today, the railroad still runs along the quiet bend of the Youghiogheny where the wreck took place over a hundred years ago.

![]()