The last month of 1922 was a rough one for Fayette County’s taverns. Though the National Prohibition Act (or “Volstead law”) was put in place nearly three years earlier, local speakeasies still offered a setting for “many Saturday night frolics and joyous pleasure parties,” as an article in the Daily News Standard called them. That came to an end for a few saloons on December 2, 1922, when court action forced them to close.

Two of the restaurants mentioned in the article, the Savoy and Columbo, appear in the 1921 city directory as Italian spaghetti houses. The Savoy was located at 38 S. Beeson Avenue, near the present day offices of the Herald-Standard, while the Columbo resided a block away at 32 E. Church Street.

Both were shut down after some police work by a State Trooper named Edward J. Koehn, who described his infiltration of the saloons in court.

Savoy’s entry in the yellow pages of the 1921 city directory.

Koehn was called in from Butler with other State Troopers to act on a lead. When an informant provided a list of “local liquor rendevous,” the officers set out to investigate. The reason for bringing in a State Trooper is clear: As an out-of-towner, Koehn was a stranger in the Uniontown speakeasies.

At the Savoy, the officer observed liquor being sold for fifty cents a glass (around $7 today) and a pint of whiskey going for seven dollars (around $98 today). The alcohol was kept in a dumbwaiter and sold out of the kitchen. Prices were similar down at the Columbo, where gin went for five dollars a pint.

Uniontown’s resident chemist, Harry Fleming, tested a few bottles at his 23 W. Main Street laboratory. Fleming, who advertised analysis of “coal, coke, brick, water, and all mineral substances,” found that the Savoy’s whiskey was 48% alcohol by volume.

Meanwhile, over at the Columbo, drinkers were getting conned. The alcohol there was determined to have been “liberally watered.”

Koehn observed both men and women drinking at the establishments, but as a non-local, he couldn’t identify anyone. His testimony still had the desired effect — at least, from the “dry” point of view:

The doors on the Savoy, Columbo and the rest will be locked before night fall and Uniontown will spend one real sure enough “dry” Saturday night it seemed certain, as the process of legal machinery proceeded to put the bars up on local restaurant life.

Elsewhere in the county, the “wets” — that is, those opposed to Prohibition — were enjoying good beer made by the persistent brewmaster Albert Basha. A previous owner of a New Salem brewery, Basha had set up shop in a Masontown building and stirred up the suspicions of the Vigilant Committee. The group watched the business closely and noticed not only the addition of guards, but also the late-night loading of freight cars and trucks with cases of beer.

Within days an injunction was filed to close the business, which a local pastor called a “nuisance.” Masontown thus became “the hotbed of one of the most tightly drawn prohibition fights in the county.”

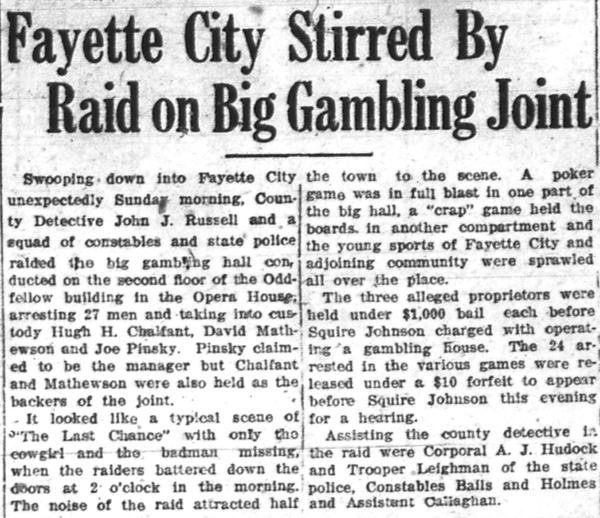

Meanwhile, gambling halls were also under siege, as evidenced by a Standard article that compared a Fayette City joint to a Last Chance Saloon:

From the Daily News Standard, December 4, 1922.

I’ve often heard that between all the bootlegging and the organized crime, Fayette County was once called “Little Chicago.” I’m starting to believe it!

![]()

To close with some more positive news, updates to the Uniontown Hospital were also completed in the first week of December 1922. Around $400,000 was raised for the improvements to previously “antiquated” structure, which the Standard called “dark, dingy and dirty,” not to mention poorly equipped.

The Standard also released a lengthy editorial about the hospital’s management, which I’ve excerpted to the right. They discussed how membership on the board of trustees was “a place of work and worry”:

On several occasions the trustees have walked into this office and told us that their new superintendents were the best ever. In about six months it was the same old story. The superintendent wasn’t worth a tinker’s dam. The staff was raising cain. The head nurses were playing ping pong. The whole kitchen was in the soup . . . They couldn’t hand us a trusteeship on a silver platter.

The public was invited to inspect the hospital the next day, with a clinic run by the Fayette County Medical Society to follow.

![]()

Many thanks to PA Room volunteer Paul Davis for digging up these articles!