It’s a little remarkable to me that, being a connoisseur of all things dark and spooky, I’d never read about Frank Monaghan until I began working here. Yes, I’d heard the man’s name mentioned in passing — typically in connection with courthouse tours. But my real introduction to his case only came after I began exploring our Rare Book Room.

The “RBR” is the temperature and humidity controlled space where we store fragile or one-of-a-kind artifacts. It’s like a treasure chest, except instead of gold and diamonds we have dusty old ledgers and newspapers from the early 1800s. (Still treasures, in my book!)

On one of the shelves, I spotted these:

These three scrapbooks chronicle the story of Frank Monaghan, a Uniontown hotelier was beaten to death by police. As noted by Richard Ball in his foreword to Screams in the Courthouse Basement, Monaghan was both “a man of notoriously shady reputation” and “a man of substance with a well-connected family.” One of his sons was a business owner in Washington, D.C.; the other was a history professor at Yale. They had the funds and the influence to ensure that the case would not get buried, but would instead gain national notoriety.

It all started on September 11th, 1936 — a particularly dark evening, lit by only a sliver of moon — when officers noticed a black Pierce Arrow weaving erratically on Old Route 119 and decided to pull the driver over.

![]()

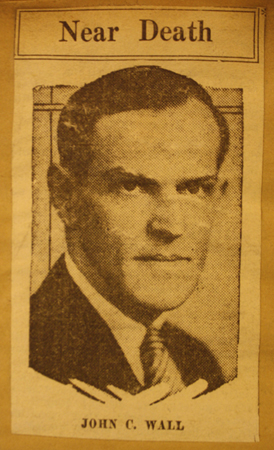

The two officials who made the traffic stop were James A. Reilly and John C. Wall — the county’s District Attorney and Chief Detective, respectively. They were passing through an area called Hogsett Cut when a swerving vehicle caught their eye. Signaling for the Arrow to stop, they pulled in front to block it and climbed out of their car. It was then that they recognized the driver as Frank Monaghan and the passenger as Florence Dean, a young chambermaid from Monaghan’s Ritz Hotel.

Reilly and Wall were certainly familiar with the 62-year-old Monaghan, who had frequent brushes with the Fayette County law in his lifetime. He had served jail time for bootlegging and had racked up a number of traffic offenses, typically due to driving under the influence. On the same day the pair pulled him over, he had been in court for ramming his car into that of another Uniontown citizen.

Monaghan was found guilty. But after the verdict was read, he was overheard saying, “I will never spend a day in jail.”

Now, after a brief conversation, Reilly judged the hotelier to be intoxicated. He suggested that Detective Wall drive the elder man and the chambermaid back to the Ritz. The pair agreed, and as Monaghan climbed into the Arrow’s backseat, Reilly returned to his car. He pulled away just as Detective Wall put the key into the Arrow’s ignition.

At that moment, Frank Monaghan drew out his penknife.

He reached forward, pulled back Detective Wall’s head, and sliced the man’s throat from ear to ear — twice.

The blade severed Wall’s jugular, as well as a number of arteries and neck muscles. The detective threw open the car door and crawled onto the road. Monaghan got out, too, walking right by his victim on his way to the blood-spattered driver’s seat. He settled in, started up the Arrow, and drove away.

![]()

District Attorney Reilly was entering the Uniontown city limits when he noticed that he didn’t see Monaghan’s car anywhere behind him. He doubled back to Hogsett Cut, where his headlights illuminated the figure of a man stumbling by the roadside with his hand at his throat. It was Detective Wall, soaked in gore and barely conscious.

As soon as he got the detective to Uniontown Hospital, Reilly contacted the city’s police chief. Both local officers and Pennsylvania State Troopers embarked on a manhunt for Frank Monaghan, but they didn’t have to look far.

They tracked him down at the Ritz, where he was just going in to change his bloodstained shirt.

![]()

Both the hotelier and his chambermaid were taken into custody for interrogation. At first, Florence Dean tried to take responsibility for the slashing, but it quickly became apparent that she was just trying to protect her employer.

Monaghan was then lead down into the basement of the courthouse — specifically, into the Bertillon Room, which took its name from the prisoner identification system used in those days. Since the attack had taken place outside of the city limits, there was a bit of an argument between Uniontown officials and the State Police over jurisdiction. In the end, representatives of both groups participated in Monaghan’s “interrogation.”

By then, more than a hundred curious citizens and local journalists had gathered outside the courthouse. Some sat very close to the Bertillon Room’s windows. Later, they’d be called “ear-witnesses” for what they overheard.

Cries for help. Pained screams. The sounds of a struggle.

It was just after 3 A.M. when Coroner S.A. Baltz and two doctors from Uniontown Hospital were called to the courthouse. There, they found Monaghan’s battered body lying naked on a cot in the Bertillon Room. They were told he had fallen in the shower.

The cause of death, Coroner Baltz claimed, was a heart attack.

![]() If Frank Monaghan had been without family, friends, or funds — a new immigrant, perhaps, who had yet to root himself in the community — one can envision a hasty burial and a clean cover-up.

If Frank Monaghan had been without family, friends, or funds — a new immigrant, perhaps, who had yet to root himself in the community — one can envision a hasty burial and a clean cover-up.

He didn’t lack any of those things.

Instead, Monaghan was a well-known businessman with two educated and respected sons, both of whom had arrived in town by morning. They had their father’s body removed to another funeral home and demanded that an autopsy be performed by a neutral party.

In this examination, the doctor observed “eleven broken ribs, a fractured right jaw, a broken nose, a battered left ear . . . hemorrhage of the brain, and internal hemorrhages due to broken ribs.” (Swimmer and Peterson, 10) What they did not find was any evidence of heart trouble. Coroner Baltz recanted on his original findings, and on September 12th, murder charges were filed against two State Troopers and Fayette County’s Assistant County Detective.

![]()

The legal battle that followed would drag on for years. Additional charges were raised against James Reilly and the Assistant District Attorney, Coroner Baltz, and even the funeral director who handled Monaghan’s body. Pennsylvania’s Attorney General stepped in and the trials were moved to Somerset County.

The legal battle that followed would drag on for years. Additional charges were raised against James Reilly and the Assistant District Attorney, Coroner Baltz, and even the funeral director who handled Monaghan’s body. Pennsylvania’s Attorney General stepped in and the trials were moved to Somerset County.

Some viewed the officers’ motivations as straightforward: Monaghan had viciously attacked one of their own, so they responded in kind. But others wondered if law enforcement had it out for the hotelier. He was rumored to be connected to the Fayette County numbers racket — in essence, a locally-run (and illegal) lottery — and if he was, he likely knew which public officials were secretly involved in the gambling ring. The theory went that he planned to blackmail them by threatening to release their names.

These scandalous rumors, in addition to the sheer brutality of the case, gathered widespread attention. The story was picked up by Time magazine and even made the news overseas, with at least one London paper keeping tabs on the proceedings.

Ultimately the two Troopers held for murder charges were dismissed from State Police. One did a short stint in prison and was paroled in December 1937. James Reilly was found not guilty and, after a brief stumble in his career, went on to serve as the judge of Fayette County’s Orphan’s Court for twenty years. Charges were dropped against all of the other defendants in the case.

Remarkably, Detective Wall survived his injuries and was able to return to work. Years later, however, he was connected to the numbers racket and fell out of favor.

Even today, Frank Monaghan’s story can raise some hackles. Use of the third-degree was certainly not unique to Fayette County at that time, but these incidents and others like them — like the involvement of the police in strikebreaking at local mines — certainly soured the relationship between the public and law enforcement.

For a much more nuanced version of this case, I recommend checking out Screams from the Courthouse Basement, reading the Al Owens columns linked in the sources below, or stopping by to flip through the Monaghan scrapbooks. For now, they’re headed back to their spot in the Rare Book Room.